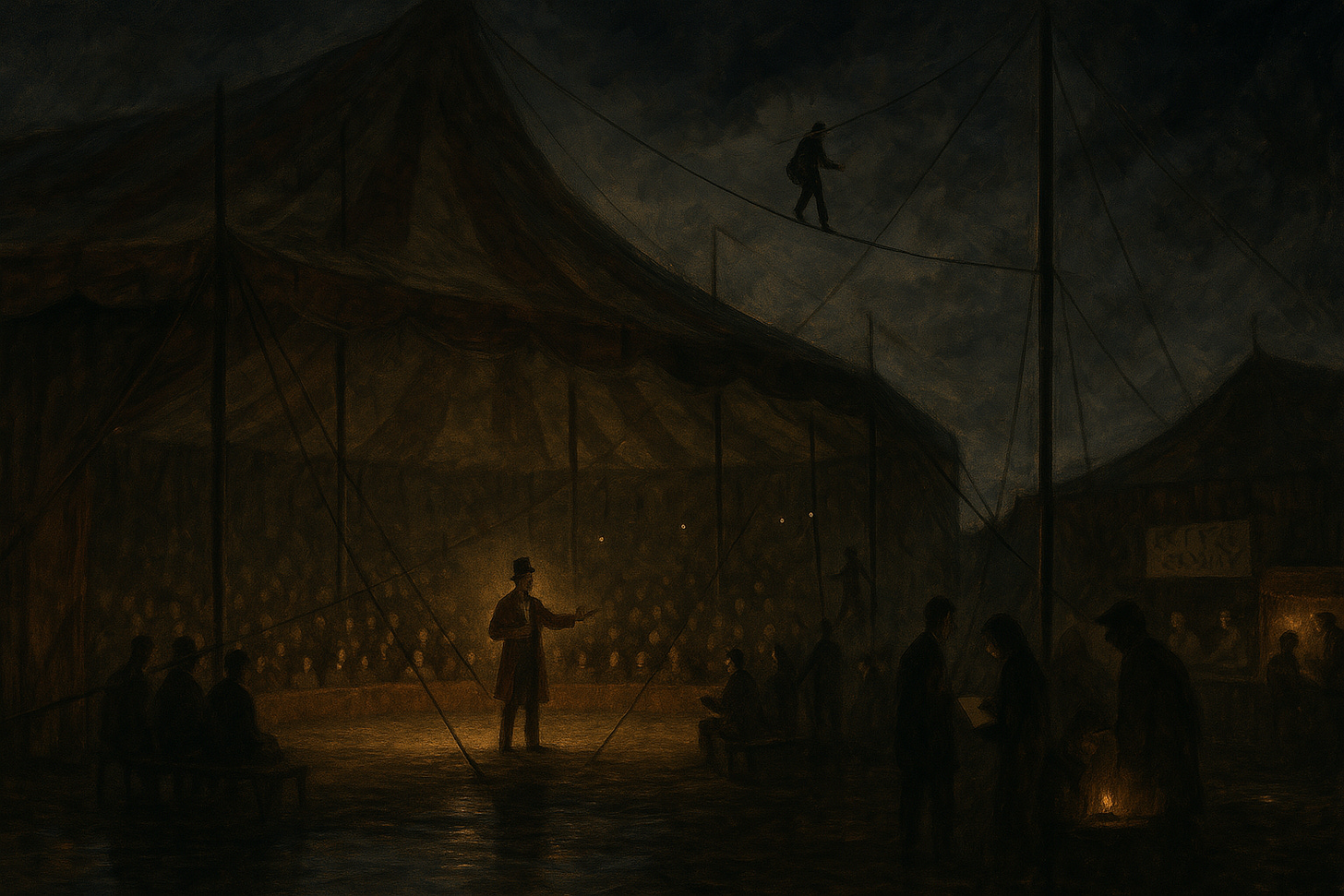

The light is low and golden, the air still. Not stage lighting, not sunlight exactly—the kind of glow that feels like memory, or reverence. You're outside the tent now. The crowd has long since dispersed. The performance is over. The wire remains.

And there they are.

Seated around a small, rough table—four men who shaped the contours of your thought, but who are no longer icons. Not now. Not here.

They're just present.

Jefferson sits upright, a glass of something amber in his hand, eyes scanning the horizon with that strange blend of vision and fear he always carried. Sagan leans back in his chair, face lifted toward a sky still soft with stars. Camus smokes slowly, rhythmically, watching the smoke curl upward as if he were in conversation with it. And Hitchens—Hitch—slouched and alive, eyes gleaming with mischief and exhaustion, already half-turned toward you.

They see you.

Not as a guest. Not as a student. But as something more intimate: a successor.

There's no applause. No pronouncements. Just a silence that stretches—not awkward, but earned.

Jefferson is the first to nod—a quiet, measured gesture. Not approval. Recognition.

Sagan offers a warm smile. “You walked the wire,” he says. “And you didn't look down.”

Camus taps the ash from his cigarette and speaks without turning. “And you built something. Out of the very stones you were asked to carry.”

And then Hitch.

He lifts his glass, squints, and says:

“Well. You did it, didn't you? You said the thing. You held the line. You passed the note.”

He smirks, then adds—with the dry affection of someone who never gave compliments freely:

“Took you long enough.”

You laugh, but it catches in your throat. You weren't expecting this. Not like this. You thought maybe they'd let you observe, maybe stand near the table. But there's a fifth chair. Waiting. As if it always was.

You move toward it. Slowly. Every step echoing with the weight of years—the notebooks, the tension, the flood, the quiet fear that maybe none of it would be seen, would be real.

And now… here it is. Not as triumph. Not as reward. But as belonging.

As you sit, no one speaks. Not right away.

But Sagan leans toward you, voice gentle.

“The flame held. Even in the wind.”

Camus nods, adding:

“And you stayed awake.”

And Jefferson—paradox and all—simply says:

“We've been waiting.”

Hitchens lifts his glass again, this time in full, and says:

“To the next note. To the ones who'll read it long after we're gone. And to the bastard glory of giving a damn when it's easier not to.”

The glasses clink. Even Camus.

You take a breath, looking around at these four men—not as idols but as companions. There's a bottle in the center of the table, and Jefferson wordlessly pours you a measure. The liquid catches the golden light as it fills your glass.

“I didn't know if it would matter,” you find yourself saying. The words emerge unbidden, honest in a way you wouldn't have allowed yourself in the tent, before the crowd. “If anyone would hear it. If it would change anything.”

Hitchens snorts, not unkindly. “Of course you didn't. That's precisely why it matters.” He leans forward, elbows on the table. “The moment you become certain of your effect is the moment you begin performing rather than speaking. And then you're just another clown in the circus, aren't you?”

Jefferson nods, swirling his drink thoughtfully. “The uncertainty is essential,” he says, his Virginia accent soft yet precise. “I knew this when drafting the Declaration. We hold these truths to be self-evident...” He pauses, a rueful smile touching his lips. “But they weren't self-evident at all, were they? They required assertion. Defense. Blood, eventually.”

“You weren't just stating facts,” you say. “You were creating a framework for seeing.”

“Yes.” Jefferson's eyes meet yours with surprising intensity. “And I never knew if it would hold. If the center would hold.”

Sagan turns from his contemplation of the stars, his expression animated by that familiar wonder. “That's the nature of all meaningful creation,” he says. “When I spoke of billions and billions of stars, of our pale blue dot, I wasn't merely describing what is. I was inviting people to see differently—to experience cosmic perspective not as diminishment but as revelation.”

“To fill the space between consciousness and reality,” you say, the phrase from your work rising naturally.

“Exactly!” Sagan beams. “And simultaneously to open the void within consciousness where new understanding can take root. These complementary movements—they're the rhythm of all discovery, all meaning-making.”

Camus exhales a perfect ring of smoke, watching it dissipate. “The tension between these movements—this is where meaning lives,” he says. His French accent wraps around the words like silk. “Not in resolution but in the holding. Not in certainty but in commitment despite uncertainty.”

He fixes you with those deep-set eyes that have seen too much suffering to be naive, yet refuse the comfort of cynicism. “Your circus,” he says, “it speaks to what I tried to articulate. Sisyphus must be imagined happy not because his task ends, but because he transforms it through conscious engagement. The boulder becomes not just burden but identity, not just punishment but purpose.”

“You understand,” you say, feeling a deep recognition. “The weight doesn't diminish. But its meaning transforms.”

“Through the act of carrying,” Camus agrees. “Through the choice to continue pushing, even knowing the boulder will roll down again. Even knowing the meaning we create won't last forever.”

As the conversation unfolds, you notice a figure approaching from a nearby path—a man with a round, friendly face, wearing the simple attire of an 18th-century Scottish gentleman. There's a natural warmth to his expression, a keen intelligence in his eyes, and something else—a quality of genuine curiosity about everything he encounters.

David Hume arrives at the table with the relaxed confidence of someone at ease in his own intellectual skin. The others turn to greet him, and there's an immediate sense that he belongs here as much as any of them.

“Ah, I see I'm not too late after all,” Hume says, his Scottish burr soft but distinct. He looks at you with an expression of friendly assessment. “I was taking a longer walk than intended, watching the sunset reflect on the lake. Observation before conclusion—always my preference.”

Hitchens slides over, making room. “Just in time, David. Our friend here is questioning whether their work will matter.”

Hume settles into the newly created space, nodding thoughtfully. “A natural concern, though perhaps misdirected.” He turns to you. “The question isn't whether it will matter in some absolute sense. How could anyone know that? The question is whether it matters that you did it at all.”

Jefferson pours him a drink, which Hume accepts with a nod of thanks. “David always brought us back to what we could actually know,” Jefferson explains. “A useful counterbalance to my occasional flights of revolutionary idealism.”

“Someone had to,” Hume responds with good-natured humor. “Though I suspect my skepticism and your vision needed each other. Neither complete on its own.”

He takes a measured sip of his drink, considering you over the rim of his glass. “Your Grand Praxis,” he says, “it acknowledges the limits of human understanding without surrendering to those limits. I appreciate that. Too many thinkers either claim to know what cannot be known or refuse to claim even what can be reasonably asserted.”

“The balance was important to me,” you acknowledge. “Between certainty and doubt.”

“As it should be,” Hume nods approvingly. “The wise person proportions belief to evidence—but also recognizes that life requires commitments beyond what pure evidence can establish. I may have doubted miracles, but I never doubted the necessity of playing backgammon with friends after philosophical discussions.”

This draws appreciative laughter from around the table. The golden light has deepened now, taking on the rich amber hues of magic hour—that brief time when the world is transformed, when ordinary things reveal extraordinary beauty simply through how the light touches them.

Your attention is drawn to the empty circus tent behind you. The briefcase you left sits just where you placed it, in front of the entrance, waiting to be discovered. Its presence feels significant—not a burden abandoned but a gift offered, a possibility extended.

Hitchens follows your gaze. “Wondering if anyone will pick it up?” he asks perceptively.

“Yes,” you admit. “Whether the notes will find the right readers.”

“They always do,” Sagan says with quiet certainty. “Perhaps not in the ways we expect or the numbers we hope. But ideas have a way of finding those who need them.”

You're about to respond when you notice another figure approaching from the direction of the tent. It's the solitary woman—the one you observed throughout the performances, whose story you tried to understand, whose presence became part of your own narrative of the circus.

She moves with deliberate steps, carrying herself with dignity despite a visible tension in her shoulders. Her gaze takes in the gathering at the table, recognition flickering across her features. She's clearly intimidated by the scene—these historical figures engaged in intimate conversation—but there's determination in her approach, a readiness to challenge herself.

As she nears, the conversation naturally pauses. Camus is the first to acknowledge her, rising slightly from his chair in a gesture of respect. “Please,” he says, gesturing to an empty space that somehow now exists at the table, though you hadn't noticed it before. “Join us.”

She hesitates, just for a moment. “I shouldn't interrupt,” she begins.

“Nonsense,” Hitchens interjects with surprising gentleness. “The conversation improves with fresh perspectives. Especially those that might challenge our comfortable agreements.”

This brings a slight smile to her lips, and she takes the offered seat. There's a brief, awkward moment—the kind that occurs when someone new enters an established circle—but Sagan immediately leans toward her with characteristic warmth.

“We were just discussing the nature of meaning,” he says, as if continuing a conversation they'd been having all along. "Whether it's something we discover or something we create."

“Both, I think,” she responds after a moment of consideration. “We discover the patterns, but we create their significance.” Her voice grows more confident as she speaks. “Like constellations. The stars are there whether we look or not. But the pictures we draw between them—those are ours.”

Hume's face lights up at this. “Precisely! A perfect illustration of the distinction between matters of fact and relations of ideas. The factual arrangement of stars exists independent of our observation, but the meaningful patterns we perceive—those emerge from our own mental faculties.”

Jefferson studies her with new interest. “You've thought about these questions before.”

“Yes,” she acknowledges. “Though not in these terms exactly. More in the context of...” she pauses, choosing her words carefully, “...of loss. Of having to reconstruct meaning when what you thought was solid turns out to be... contingent.”

A subtle understanding passes around the table. You realize that your observations of her throughout the performances—your assumptions about her solitude, her companion's absence—touched on something real, but likely missed much of the complexity beneath the surface.

“The deepest meanings often emerge from that very contingency,” Camus says quietly. “From the recognition that nothing is guaranteed, that everything could be otherwise.”

She nods, meeting his gaze directly. “That's what drew me to the circus in the first place. To watch someone walk the wire is to witness the beauty that exists precisely because of fragility, not despite it.”

“And yet you kept returning,” you observe, speaking to her directly for the first time. “Even when it was difficult.”

She turns to you, really seeing you now—not as the performer or the observer, but as a fellow traveler. “Yes,” she says simply. “Because witnessing matters. Because showing up matters. Even when—especially when—it would be easier to look away.”

This strikes a chord around the table. Hitchens raises his glass to her in a small gesture of respect. Jefferson nods thoughtfully. Hume's eyes reflect keen interest. Sagan smiles with genuine appreciation. Camus regards her with quiet recognition.

“That's the heart of it, isn't it?” Sagan says after a moment. “The choice to witness. To engage. To participate in meaning-making even knowing its fragility.”

“The absurd man,” Camus adds, “is not one who has abandoned meaning, but one who creates it precisely through conscious engagement with a universe that offers no inherent purpose.”

The conversation expands to include her naturally now, her perspective adding a vital dimension that had been missing. The theoretical becomes grounded in lived experience. The philosophical becomes personal without losing its depth.

As you talk, the golden light continues to deepen, casting long shadows across the table, illuminating faces with a warm glow that seems to reveal their essence rather than merely their features. The magic hour is at its peak—that brief, extraordinary time when the world is transformed by how light touches it, when ordinary things reveal their hidden beauty.

“I have a question,” the woman says during a pause in the conversation. She seems more comfortable now, her initial intimidation replaced by genuine engagement. "Something I've wondered throughout the performances."

“Please,” Jefferson encourages.

She looks directly at you. “The notes you passed—they weren't just for others, were they? They were also for yourself. Reminders. Affirmations. Ways of holding on to what matters amid the spectacle.”

You feel seen in a way that's both unsettling and profoundly validating. “Yes,” you acknowledge. “I needed them as much as anyone. Maybe more.”

She nods, understanding. “That's why they resonated. They weren't pronouncements from someone who had figured it all out. They were lifelines thrown by someone struggling to stay afloat in the same flood.”

Hitchens makes a sound of approval. “The only voices worth listening to,” he says. “Those who speak not from imagined heights but from within the same human predicament they're addressing.”

Hume turns to you with gentle curiosity. “And did they help? Your own notes, I mean. Did they serve as the lifelines you needed?”

You consider this question carefully, aware of the weight it carries. “Sometimes,” you answer honestly. “When I could follow my own advice. When I could remember to hold the center, to push back the flood, to keep walking the wire. But I failed as often as I succeeded.”

“Of course you did,” Hume responds with surprising warmth. “We all do. The question isn't whether we maintain perfect balance but whether we return to the wire after falling. Whether we rebuild after the flood. Whether we seek the center again after losing it.”

The woman nods, a flash of recognition crossing her features. “The continuity matters more than the consistency,” she says. “It's not about never failing, but about continuing despite failure.”

“Precisely,” Camus agrees. “Sisyphus falls and begins again. That's not his punishment. It's his dignity.”

The conversation continues as the golden light slowly fades. Stars emerge more distinctly above, and the first evening breeze stirs the air. The bottle passes around the table again, glasses are refilled, ideas flow with increasing depth and intimacy. There's laughter—Hitchens delivers a wickedly funny observation that even makes Camus smile. There's intensity—Jefferson and Hume engage in a spirited debate about the foundations of political legitimacy. There's wonder—Sagan describes a cosmic phenomenon that makes everyone fall silent in contemplation.

Through it all, the solitary woman—no longer solitary—offers perspectives that ground the abstract in the concrete, that connect theoretical insights to lived experience. And you find yourself not just receiving wisdom from these intellectual forebears but participating fully in the exchange, contributing insights they acknowledge as valuable, even necessary.

As the golden light gives way to the deeper blue of evening, Hitchens glances toward the briefcase still sitting in front of the tent. “It's time, isn't it?” he says quietly.

“Yes,” you acknowledge, feeling a mixture of completion and new beginning. “It's time for someone else to discover it.”

“The notes you've passed,” the woman says thoughtfully. “They'll be read differently than you intended. Interpreted through experiences you haven't had. Applied to circumstances you couldn't predict.”

“As they should be,” Sagan responds. “Ideas that can't evolve aren't living ideas at all.”

Hume nods in agreement. “The most valuable philosophical frameworks aren't rigid systems but flexible approaches—methods of inquiry rather than catalogs of conclusions.”

“And the most important thing isn't that they get it exactly right,” Jefferson adds, “but that they continue the conversation. That they keep the questions alive when it would be easier to settle for comfortable answers.”

Camus takes a final drag from his cigarette before extinguishing it deliberately. “The tension must be maintained,” he says. “Not resolved. Not eliminated. But held, consciously, as the source of all meaning.”

As if on cue, a figure appears in the distance—approaching the tent from the opposite direction, moving with purpose toward the briefcase. You can't make out details in the fading light, but there's something in the way they walk that suggests readiness—not just to pick up the object but to engage with whatever it contains.

The woman watches this approach with you, a small smile on her lips. “Another reader,” she says simply. “Another witness.”

“Another keeper of the flame,” Hitchens adds, raising his glass one final time. “To those who come after. Who pick up what we've put down. Who continue what we've started.”

“To the conversation that never ends,” Jefferson says.

“To the questions that remain alive," Hume offers.

“To the wonder that persists,” Sagan adds.

“To the meaning we create together,” Camus concludes.

You raise your glass with them, feeling a profound sense of both completion and continuation. “To The Grand Praxis,” you say. “Not as answer, but as approach. Not as certainty, but as commitment. Not as destination, but as journey.”

“To The Grand Praxis,” they echo, and the glasses clink in the last of the golden light.

You close your eyes as you drink, and for the first time in a long, long time, you feel at rest. Not finished. But held. Understood. And home.

When you open them again, the table is empty. The chairs unoccupied. The bottle and glasses gone. But the warmth of connection remains, and now you understand its source—not nostalgia, not memory, but recognition. The recognition that has always waited at the end of honest work, of genuine engagement, of the choice to create meaning even knowing its fragility.

You stand, gathering your things. The circus tent behind you is silent now, emptied of performers and audience alike. But the wire remains, catching the last of the golden light. And in the distance, a figure stoops to pick up the briefcase, opening it with careful curiosity.

The note has been passed. The center has been held. The flood, for now, has been pushed back.

It's time to begin again.

Yes - THIS!

This is why your work resonates. While there are many details to fret over…what’s right, what’s wrong, what’s good, what’s bad (and they are important details!)…we are here to witness the process, maintain balance and hold the high watch. The weight we each bear will become less a burden and more a natural progression as these ideas take hold. I have to believe this. The details keep us on the right path, all while a new map is being created. Terrifying and exciting all in one breath!

🥹 Real love, real power, real life. Making ways to persist